White Minneapolis residents who care about education, in whose numbers I count myself, are adept at highlighting the systemic designs that serve as barriers to students of color in our community. We are less reliable in applying the same level of analysis to the systemic designs we use to sustain our own positions of advantage.

One tool we use to perpetuate that advantage with brutal effect is the intersection of housing and education. If we have any hope of achieving a just and democratic community, these tools must be dismantled. This means eliminating the current systems that assign students to schools (and exclude them from others) using students’ home addresses.

There is a long and well-documented history of racism in housing in our country and in our community. It involves the collusion of the federal government, home loan institutions, and individual citizens.

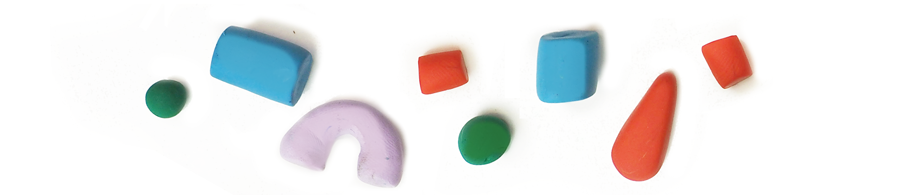

In the early- and mid-20th Century, the Federal Housing Administration began to insure mortgages in an effort to boost home ownership and grow the middle class. But the program was plainly racist. The FHA created maps that defined where and how they would insure mortgages. White neighborhoods were colored blue and green, and were given the highest rating for lending purposes. Black neighborhoods were colored in red, and were effectively denied the support of the federal government.

This redlining was done in collusion with lending institutions, which used and contributed to the FHA’s maps.

But it wasn’t just the government and lending institutions that reinforced segregation in Minneapolis. Individual homeowners, seeking to ensure the White racial purity of their neighborhood included “racial covenants” into their home deeds that prohibited anyone other than a White person from ever owning the home.

The site Mapping Prejudice provides a visualization showing racist housing covenants metastasize across South Minneapolis through the 1960s, forcing Black residents to crowd into the concentrated pockets in North Minneapolis the covenants failed to infect.

These are not merely historical phenomena. A 2014 study found that high-income Black people in the Twin Cities were about 3.8 times more likely to receive a subprime loan than low-income White people. And the examples of racism in modern lending institutions in our community are manifold.

The reality of who can live where and who can’t is so corrupted by this generations-long history of White supremacy that any system that uses that distribution as a primary reference is necessarily corrupt itself.

And yet that’s precisely how we decide who can attend which schools.

Here are three maps of the city. The first map, from Mapping Prejudice, shows the spread of racial covenants in homes through the 1960s. You can see how the covenants excluded people of color from Southwest and Southeast Minneapolis, pushing them North. In the second FHA map, neighborhoods outlined in green and blue are noted as “best” and “still desirable,” while the yellow is “definitely declining” and red is “hazardous.” Again, you can see how White residents in Southwest and Southeast excluded people of color to the red and yellow sections of North Minneapolis. The third map shows the current attendance zones for MPS—one zone for Southwest, one for Southeast, and one for North.

We’re not even subtle about this. When you search for a home on Zillow, there’s a “Schools” filter with data and ratings from Great Schools built right in. In this country, we purchase our way into schools.

There is no moral, ethical, or democratic justification for using housing as a means of allocating access to public education. The conversation should not be about how to draw more equitable zones, or how to better manufacture games of chance that allow some people to enroll across zones, but about how to get rid of the zones altogether.

And yes, this would have to expand to include districts, themselves. Because all these racist housing machinations were used not just in the city itself, but with equal zeal by White people fleeing to wall themselves off in the suburbs.

School access boundaries, whether attendance zones within a district or the bounds of the district itself, are drawn for one reason: to exclude.

So, then, if we can’t use housing to assign schools, what do we do? I’m not sure, but I’m confident that if we started from the assumption that we can’t use race, income, or housing (which, in the end, is a proxy for the first two) as a reference, we’d figure it out. Maybe we have a statewide lottery. When your number gets pulled, you get to pick your school—any school in the state. Maybe we try to infuse some small amount of recompense in the system and Black families get five-thirds as many lottery entries as White families. And maybe Indigenous families just get to pick first.

I don’t claim to know what the best system is, and I’d be the wrong person to decide. But I do know that our current practice of drawing lines around neighborhoods we know were created in the image of White supremacy has to end.

To be clear, this will not “solve” the problem of schools miseducating Black, Brown, and Native students. It will not suddenly instill the disproportionately White teaching force with cultural competence, it will not imbue schools of education with programs founded on justice, it will not rend the dominant curricula from their Eurocentric focus.

But the current system is indefensible, and I have no optimism in our ability to achieve educational equity while it stands. We certainly need to continue to talk about the systems and structures that disadvantage students of color in our community, but we also have to embrace the reality that those systems and structures are one in the same with the systems and structures White people use to preserve our positions of advantage. If we truly want to bring down the systems of injustice in our community, they all have to come down together.

Contributors