Words by Meher Khan

Minneapolis is looking a little different lately. It’s probably the giant banners, billboards, projections, and posters going up, using cheeky imagery and unsettling statistics to call out inequities wherever they may be lurking. This is the work of a group of women artists who have made it their mission to uncover inequities in the art world, and they do it in singular style and gorilla masks. If ever there were true masked avengers, the Guerrilla Girls are it.

For over thirty years, the Guerrilla Girls have been creatively protesting the lack of representation of women and people of color in the art world. Their gorilla masks protect their identities as they confront prominent people in the art world, but also serve to put their guerrilla work in the spotlight, rather than themselves. Their work has led to invitations to speak at numerous colleges and universities, and sometimes even the museums they criticize. This week, the Guerrilla Girls are busy visiting art spots all around Minneapolis and St. Paul for their Twin Cities Takeover. Kathe (named after printmaker Käthe Kollwitz) and Frida (Kahlo) very kindly took some time to meet with me at the Hennepin Theatre Trust, and shared with me the origins of their group, their past and present work, and some advice on starting your own masked avenger group.

How did the Guerrilla Girls come to be?

Käthe: In 1985 we were young artists, and we realized that most of the opportunities and almost all the money were going to white male artists, and no one seemed to care. So we took it upon ourselves to strategize a way of making that an issue that people talked about and perhaps institutions would change. And thirty years later, we’re still doing it.

Frida: We almost immediately branched out into other areas of culture, politics, issues of all kinds of discrimination.

What kind of environment were you up against?

Frida: It was different in 1985. Women and artists of color weren’t even considered good enough to be shown in galleries or museums. Everyone thought the art world was a meritocracy. Well, I think that’s in the past. No one would ever say that. But now the art world is a lot about money, and about paintings and artworks that sell for hundreds of millions of dollars, and we all know that people who consume that are, you know, billionaires, and kind of an oligarchy. And we question whether allowing money to define art is a proper way to record our culture.

Because if all the voices of the culture aren’t in the history, it’s just a history of power and money.

What kind of work do you make?

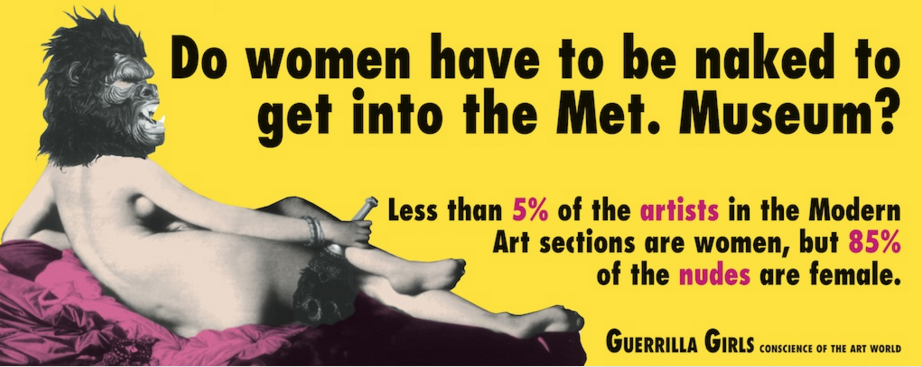

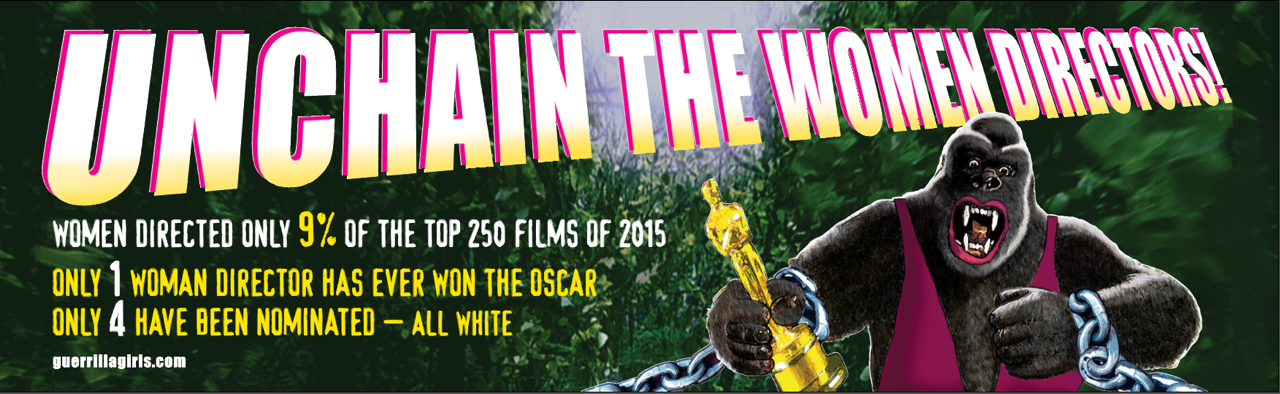

Käthe: We had this idea to do a new kind of political art and kind of thought up a slightly different way than it’s usually seen. Most political art points to something and goes, “This is bad.” And although that may be something you realize when you see artwork, what we do is, we try to find a new way into an issue. We try to twist it around and present it with a really in your face, unforgettable headline, visual, and then statistics to back it up. And a good example of that is probably our most well known poster. I mean there are many good examples. There’s a good example on Hennepin Avenue and 9th Street right now: the anatomically correct Oscar. He’s white just like most of the guys who take them home. And then there are all these statistics about #OscarsSoWhite kind of statistics. But our most well-known poster is called, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?” So basically, we were trying to show that there was hardly any art by women artists hanging in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. But we didn’t do a poster that said, “There aren’t enough women at the Met.” We did a poster where we took a painting by Ingres, put a gorilla mask on her, and said, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?” And then paid it off with a statistic: Only 5% of the artists in the modern art sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female. So it makes a comment about the museum, about art, and also about the way women’s bodies have been splashed all over the place for so many centuries.

We have this strategy that worked, and we just keep applying it to lots of different things. And we always try to deepen our critique, and we’re a group of artists, so we’re always trying to experiment with this and experiment with that, but basically, we did stick with the strategy that worked.

Frida: We started doing posters but we’ve also done billboards, we’ve done interactive projects, we’ve written five books, and we do hundreds of appearances at colleges, universities, art museums—some of the very museums that we criticize ask us to come and do presentations of our work, which is pretty bizarre.

Käthe: The weirdest thing is we’re these agitating outsiders and after so many years of doing it, our work is in a lot of the museums we criticize. Like at Mia right now we have an entire project casting a very critical eye in our own crazy style on their collection.

Frida: I mean there are lots of well-intentioned people who are in entrenched institutions trying to change them, and it can’t happen overnight, or doesn’t happen overnight. But there are people trying to turn that boat around, so we’re really pleased when we get an invitation like that to come inside and actually criticize the museum on its own walls.

How do you fight against most funding going to larger, predominantly male, white institutions over grassroots organizations—especially organizations led by people of color?

Käthe: Well, first of all, like Donald Trump, we are self-funded.

Frida: That’s the only thing we have in common with Donald Trump. Except fake hair.

Käthe: We sell books and posters to people, we get paid to make appearances. So we don’t get grants. That’s number one. But yeah, how can you break through? I think one thing that would be really great is for some anonymous group, like us, to run those statistics. And we just did this in Iceland. So in Iceland we did this billboard, and this was about film. We found out that almost all the films in Iceland are funded by this national film center, and almost none of the awards to make your film are given to female filmmakers. So we did this big billboard about it with the statistics and all this stuff and it had a funny questionnaire, kind of satirizing the fact that in Iceland their legislature has a very high percentage of women. But in the arts, same old same old.

Do you have advice for emerging women artists?

Frida: Well, you gotta love your work, and you gotta realize that even though the system might not be set up to accept what you do, it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it. You’re part of a cultural continuum, and shouldn’t take no for an answer. Don’t do your work according to other people’s expectations of you.

Käthe: Luckily, you can’t stop artists from doing their work. It’s really hard.

Frida: You can frustrate them.

Käthe: Yeah, you can demoralize them, there are things you can do. But artists are going to make art, and we’re so lucky that that’s true, because without that, we’d have no culture.

What’s a favorite project of yours, or something that’s been impactful?

Frida: Well, when we wrote our first two longest books, Bedside Companion to History of Art and Bitches, Bimbos and Ballbreakers, I just love doing the books. I just loved it. And when I realized that you could actually research a book on stereotypes by surfing the Internet, that was really exciting [laughs]. You didn’t have to spend hours in a library, and there were keyword searches and all of that. So that was sort of my favorite project because it was extended, it was long-term. When we’re doing these books, I love the process of putting together a book. It was long, it was detailed, it came out with a product that you could just hand around, and all of a sudden they became textbooks in schools. That was really exciting.

Käthe: Last spring was our 30th anniversary and, in celebration of it, we did a huge sticker campaign, and a sneaking-around New York projection campaign about income inequality kind of filtered through billionaires controlling art. So it was about the horrible art system, and about the system at large, and one of the first images of this campaign is a poster that says, “Dear Art Collector: Art is so expensive, even for billionaires. We completely understand why you can’t pay all your employees a living wage.” So again, it combines two different things, and you won’t think about the art world the same way after [you see it], if you pay some attention to it.

Are you hoping to inspire a similar change in the next generation?

Käthe:

We don’t need to inspire it, it’s happening.

I mean it’s kind of a fantastic age of activism. It doesn’t mean that everyone’s out on the streets doing things, but there are so many horrible problems right now. There’s just been an outpouring of all kinds of activism about so many issues: Black Lives Matter, trans issues, xenophobic issues, anything this horrible fucked up government we have, etc. And even when you go to a demonstration now, you see the most creative, incredible banners, objects, posters, that people bring to these things. So, of course, there’s still people who haven’t stepped up, but it would be great if more and more people stand up for what they believe in every second of the day.

Frida: I also think there’s a development among young artists, in particular art students, that really don’t accept the old model of find your style, find your gallery, sell your work to a lot of rich collectors, get in museums, and you know, become a genius. I think a lot of young artists are frustrated with that model and really want to find new ways of using their skills, their creative thinking, to deal with social problems. And that didn’t exist thirty years ago.

Do you have any opinions on the art climate in the Twin Cities?

Käthe: You know, we’re going to know so much more at the end of this week than today, because we’re going to be going around to all of these exhibitions that are part of the [Twin Cities] Takeover, so I would say I really don’t know enough about it. I know it’s a city that really values culture more than many other cities do. But I just don’t know enough to make any kind of statement about it.

Frida: Well, something that could be said is that some of the institutions are not as diverse as the communities are.

Käthe: Well, that’s true, that’s good, and that’s true everywhere.

Frida: There are many populations in the Twin Cities that are not represented at Mia, for example. On the other hand, this whole takeover came together so well because there’s a community of organizers who took care of it. We’ve never done anything like this before. Within a year, they had all these activities set up, they worked well among each other—that part was pretty amazing. So there is a sense of community, I think, within the art world. Whether that filters to the institutions, I’m not sure.

How do you get into the large institutions?

Frida: It was sort of all done for us, but both those institutions [Mia and the Walker Art Museum] are run by women, and also, I mean I think if there’s an interest in our work, I mean if we’re invited somewhere, we’re invited to make trouble. And that’s what we do.

And people are receptive to you usually coming in and..?

Käthe: Not as much as here!

Frida: And who knows what the entire institution feels. You know, sometimes you have to be really clever to get a foot in. Someone inside the institution has to be clever to get them on board to support something like we do. So they figured out how to do it.

Käthe: But what was interesting was we did this animation that’s in the museum, which is a kind of critical analysis of their collection, without pointing fingers at any individual administrator. It’s just a fact. They don’t have enough Hmong work, they don’t have enough Somali work, they don’t have enough African American work, they don’t have enough work by females! And we put it up, and all of a sudden, they showed Rosa Bonheur’s Palette.

Frida: They put it on exhibition.

Käthe: They increased the number of Somali additions. I think we were a little proactive that way. We forced them to make, not enough changes, but some kind of change. So I guess it’s up to the rest of the community to keep up the pressure. And we’ll come back to tighten the screws. If we’re invited.

At this point, they showed me the video of their projection that’s currently on display at the Mia on Käthe’s phone.

Käthe: This is a big projection that’s up [at the Mia].

Frida: And it’s also being projected outside downtown Minneapolis this week.

Käthe: Yeah, every night, it’s just down the street [from the Hennepin Theatre Trust].

That’s incredible…there’s only two pieces by Somali artists.

Käthe: Well, actually, they’ve since put up three more Somali works.

Since you’ve put up your video?

Käthe: Yeah [laughter], but there were two when we did that.

Frida: And the Somali works are all from Somalia, right?

Käthe: Yeah, I don’t think there’s any Minneapolis Somali work up right now.

And also this was an interesting project for us because we’ve done the books, we’ve written all these books where we go much deeper into something and you can have a lot more text and information, and then a poster of ours or a billboard of ours is so simple. You know, it has to be a really quick shot, and this is like an in-between thing, so I think we’re going do something in this same kind of form—not the same kind of content—for some exhibitions we have coming up in Europe.

Do you feel that art is the best way to address all of those inequities that are happening?

Käthe: I’m not sure.

Frida: You mean, what we do is the best way?

Yeah!

Käthe: No, we’re a group of artists, and we do something that works in its own way. But everyone has to do it their way. I think the issue is we need lots of us to keep up the pressure. There have to be people keeping up legislative pressure, you know, there has to be all kinds of things. I don’t know, we’re kind of the creative complainers who point things out that maybe people haven’t noticed before, and we hope that we can change people’s minds.

Frida: Yeah I mean we do get letters from people in very diverse fields saying: Your posters aren’t only about the art world, they’re about my life too, these people, you know, in veterinary science, in cartooning, in music, in mortuary science, you know—crazy, unrelated fields. And I don’t know that that says art is the best way to change things, but it is one way, and it’s the world that we know the best.

Käthe: We’ve done more about the art world than anything else, but we just were in Sarajevo at a feminist festival that had all kinds of people. It’s just crazy. We’ve got almost a hundred thousand followers on Facebook, and they certainly are all kinds of people. And also our work is taught in so many schools, even in high school now. And certainly in lots of colleges, and that’s made a real difference too, because I think people, you know, students see this work and they get inspired to do their own thing.

How does one become a Guerrilla Girl? (I had to ask!)

Frida: Well, the bad news is there’s kind of no way to become a Guerrilla Girl. We find people who we know. If we entertained everyone who wants to join us, we would be a full-time employment agency. That’s the bad news. But the good news is if you want to do something like the Guerrilla Girls, you don’t need us! You can get together with people who you can work with, who agree with you, make up your own crazy organization, and use us a model!

The world really needs more than one feminist masked avenger group.

Is there anything else you want the Pollen community to know?

Kathe: Well, I think we’re on a great frontier of gender examination. And I think that the landscape of gender difference and gender equality ten years from now is going to be something we can’t even imagine now. It is the next frontier. And we’re looking forward to it, we’re going with it, and we think that no one is free until everyone is free, and women, men, GLBT, trans people, are all going to be liberated. Let’s hope.

Our group is a feminist group, feminist avengers, etc., but we’ve always believed in a very wide definition and feminism being about fighting for human rights for all. And that of course includes your constituency, every group of people really in the United States. There are so many issues, but it’s all about more human rights for everyone, everywhere, including in the United States.

To catch the Guerrilla Girls on their Twin Cities Takeover, check out some of the locations where their work will be display, and don’t miss their show at the State Theatre on Saturday, March 5. Visit ggtakeover.com for details.

Special thanks to the Guerrilla Girls and to Joan Vorderbruggen and Kevin Vollmers of the Hennepin Theatre Trust for making this interview possible.