Hope Community is based in the racially diverse, low- and moderate-income Phillips neighborhood of South Minneapolis. The organization works with community members and is known for its groundbreaking model of continuous engagement. Over 1,000 youth and adults work with Hope Community each year to build stronger lives and more power for their families and communities.

THE PARK in the Phillips neighborhood should have been a bustling green space where families strolled and kids went to play, but the area was rampant with crime. The whole neighborhood looked like a place that had been forgotten. Deserted gas stations dominated a four-corner intersection, and house after house sat abandoned and empty. After years of violence, neglect and soaring drug use, the city seemed to have given up.

By the mid-90s, few saw a promising future for the Minneapolis neighborhood, and no one wanted to invest in the area. Yet, in a time when challenges drove more people out than in, one organization chose to stay: Hope Community. For 15 years, the nonprofit operated a small women’s shelter, St. Joseph’s House, in the neighborhood about a mile south of downtown Minneapolis. In 1996, the staff decided to close the shelter’s doors in favor of pursuing a more ambitious and all-encompassing mission: to reclaim the neighborhood with its residents.

Hope Community built housing, developed community spaces and supported local businesses. Through it all, the organization put community members at the center of its revitalization work, letting them redirect the neighborhood’s course to design a space where they could see a future.

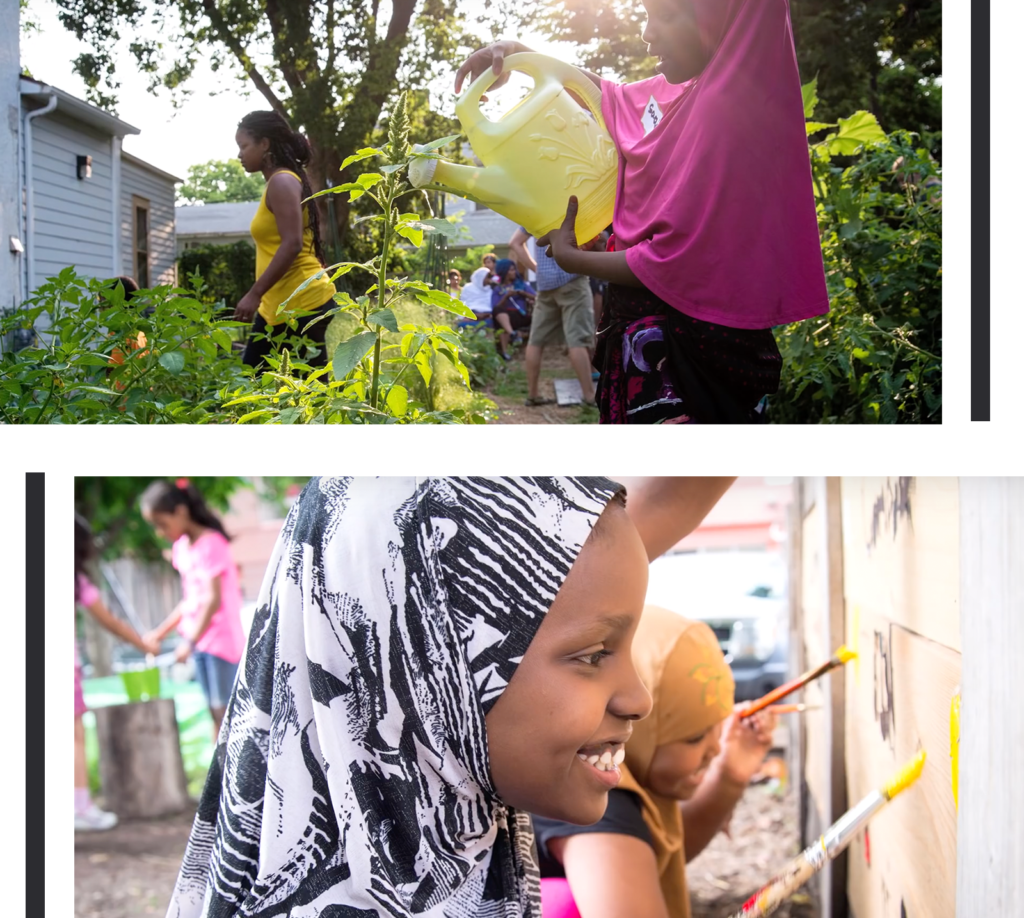

While many nonprofits rely on their own expertise to address social problems, Hope Community knows that systemic change only happens when you engage the people most affected by the problem. To tackle the boarded-up houses, overgrown yards and poor lighting at the intersection of Franklin Avenue and Portland Avenue, Hope Community treated community members as experts. Rather than creating a development plan and presenting it to residents, Hope Community went to the neighborhood and asked, “What do you want to see here?” Those responses shaped the transformation of the space into a mix of affordable and supportive housing, playgrounds and gardens.

“We acknowledge and develop the resilience that already exists in the community,” says Chaka Mkali, Hope Community’s director of organizing and community building. “Our approach is asset-based as opposed to deficit-based. It’s about how you engage the community in enhancing the quality of their own lives and a belief in people’s ability to do for self.”

A single program doesn’t define Hope Community. What sets the organization apart is how it approaches each project it opts to undertake. The group isn’t chasing solutions to problems, but is committed to growing and nurturing a strong base of community leaders that can step up, learn together and drive forward a vision for the community.

“People are not empty vessels for me to pour something into,” says Chaka. “They have something to give. We know people as active participants shaping their lives, not clients who are broken and need to be fixed.” Letting residents in the Phillips neighborhood guide Hope Community’s work starts with constant communication. Each year, it meets with hundreds of community members in one-on-one meetings or through group listening sessions. Any project, whether it’s a camp readiness program or a community garden, is informed by what staff hear during these community gatherings.

While occasional listening sessions will have a specific theme, Hope Community doesn’t set a formal agenda. Staff members intentionally ask what changes residents would like to see in the community and how they’d like to be involved. Hope Community then works together with community members to organize and facilitate meetings, and to collectively debrief after each session. By reporting back to members, Hope Community develops trust with residents and reassures them that it heard and understood their concerns. “I believe the longevity of Hope has much to do with us not imposing ourselves on community, but being in community with our neighbors,” says Hope Community executive director Shannon Jones. “Utilizing our resources to support the dreams and hopes our neighbors have for this community.”

In an early listening session, staff members asked the Phillips neighborhood, “If you could do any kind of community building work with your neighbors, what would it be?” An overwhelming majority favored a community garden. Hope Community invited interested community members to organize around the project. Through one-on-one meetings, it learned people weren’t happy with the initial, self-organized structure in which leadership defaulted to a single community member. To remedy the situation, it invited participants to imagine a new structure that worked for them. It took the ideas and established a new structure where gardening mentors, sourced from the community, worked alongside small teams in the garden.

Hope Community is committed to in-person listening because it recognizes community members as the most valuable set of experts to resurrect the Phillips neighborhood. They set the direction for its work and implement projects, even if that means the organization needs to slow down progress on an initiative to provide additional coaching or training. For Hope Community, leadership isn’t about an individual who holds a position of power in an organization, but someone who asks for more responsibility, wants to learn and gets things done. As a leadership incubator in South Minneapolis, the organization invests in transforming residents from people who simply participate in a project, into people who engage in deeper relationships, advocate for themselves and others and eventually take on a larger role in the community.

“Building confidence is the foundation of what we do,” says Andrew Hopkins (“Dhop”), Hope Community’s director of youth and family engagement. “Kids need to learn to read, but even more importantly they need to build their confidence so they can keep learning and ask for what they need.”

Hope Community puts as much emphasis on leadership development as it does on specific project outcomes, creating a more transformational impact that better positions the community to lift itself up, no matter what challenges come its way.

While many organizations subscribe to a traditional leadership structure with an executive director and department leads, Hope Community realized it needed something different. In the late 2000s, it saw a growing disconnect between staff who worked in the field and the management team that guided the group’s overall operations. To bridge the divide, it explored alternative leadership structures.

“The people who were out there creating the future of Hope Community weren’t in the room,” says Mary Keefe, former executive director of Hope Community. “We said, ‘We need these folks in the room.’”

Hope Community scrubbed its conventional management structure and replaced it with a new model called the Action Team. The group consists of the organization’s executive director and lead community engagement staff. Each week, the group meets to share progress, solve problems and identify opportunities for collaboration on individual projects and programs. The Action Team creates a unique platform for staff working directly in the community to work in concert with management staff on day-to-day strategy and long-term organizational goals. It also allows staff to better share leadership and power when working on a range of issues like budgeting and filling building vacancies. The restructuring ensures that the organization keeps resident-generated ideas and feedback central to the decisions it makes.

“This is a model where people actually have input,” says Dhop. “Often in these organizations we have blockage. ‘Senior manager’ implies hierarchy. With the Action Team, the people who are doing the work have a say in the structures and what else is happening.”

In addition to a creative management strategy, Hope Community relies on a network of nearly 30 private and public organizations to accomplish its work. Its longest running relationship with its development partner, Aeon, dates back 16 years. Hope Community’s approach to creating and maintaining successful partnerships is “a little like dating someone before marrying them,” says Betsy Sohn, director of fund development and evaluation strategy. It starts by learning more about the potential partner, such as how the organization aligns with Hope Community’s mission, what it struggles with, what its goals are, how it works internally and externally with others, how it resolves conflict and how the organization defines success and failure. After the vetting process, Hope Community may launch a small pilot program with its new partner to test how well the organizations work together. While it advocates for compromise in developing relationships, it’s intentional about selecting partners that match its values and can provide resources to achieve community goals. “All money isn’t good money,” says Chaka. Dhop adds, “We compromise, but not to the point that we’re doing something we don’t want to do.”

As Hope Community looks ahead, eyeing threats such as gentrification, it does so with the understanding that it is battling systemic, generational and institutional disengagement and racism. Its goal is to build capacity and understanding among community members to effectively challenge these systems. In this way, Hope Community activates residents in the Phillips neighborhood to commit to lasting engagement that has the power to transform the community where they choose to stay.

Produced in partnership with the Bush Foundation

to showcase the culture of innovation

behind its Bush Prize winners.

Contributors