AN INNOVATION STORY ABOUT THE

Cannon River Watershed Partnership

BY VICTORIA BLANCO

Birch trees and pine trees stand tall where the Cannon River begins flowing at Lake Tetonka. As the waterway follows its 112-mile trajectory through southeastern Minnesota toward the Mississippi River, its waters change from placid to wild.

Anglers know where to catch northern pike and bluegills; whitewater enthusiasts tumble over the rapids; and farmers irrigate their crops with the water. Yet every year, hundreds of gallons of untreated sewage leach into the water that communities in the watershed rely on, devastating the ecosystem. Sewage surfaces in residents’ backyards, and pathogens in the drinking water make people sick.

State agencies have sent engineers to assess problems in the Cannon River Watershed and implement solutions without seeking community members’ input, but the traditional top-down approach hasn’t worked. Sometimes state agencies fine communities for wastewater mismanagement, not understanding that many of these communities lack the resources to sustain newly implemented water solutions. In addition, wastewater management can be a lucrative endeavor for government agencies with the power to fine. Often, engineers approach communities and offer to assess for free, then charge too much to fix the problem. “There’s a fear of cost and impact,” explains Aaron Wills, a community wastewater facilitator and finance director for Cannon River Watershed Partnership (CRWP). “People don’t need fines; they need help.”

Treating water and protecting the health of communities is top priority for CRWP. Founded in 1990, CRWP currently serves 21 low-income counties in southeastern Minnesota.

Communities that come up with their own water treatment plans continue to maintain the infrastructure and protocols they implement, ensuring clean water for decades. To do that, the organization invites trained community wastewater facilitators from the University of Minnesota Extension School to spend months listening to community members’ concerns and building relationships. As the facilitators gain community trust, they invite members to public forums to openly discuss wastewater problems and propose solutions. Through these forums, facilitators help communities form a task force—a team of community members who often have no wastewater management knowledge. Together, they find solutions that best meet the individual needs of their community.

CRWP finds that community engagement builds trust in the wastewater solutions, solidifies relationships between neighbors and creates a culture of investment in clean water.

CRWP welcomes everyone to the task force, aiming for a minimum of five members and encouraging diversity in gender, age, class and race. It doesn’t matter that community members know little about ecosystems and wastewater treatment; through its collaboration, CRWP provides ample education. Its number one priority is making sure task force members feel included. “They need a system they can manage and that they’re on board with taking care of. They need to feel invested in the solution,” says Aaron. Communities that discover their own solutions maintain infrastructure and protocols over the years, ensuring that water solutions last decades.

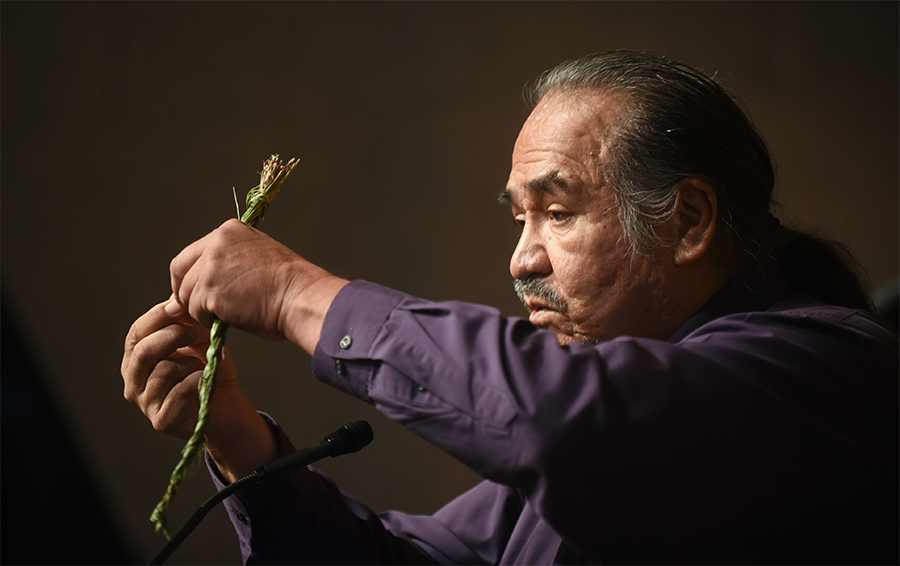

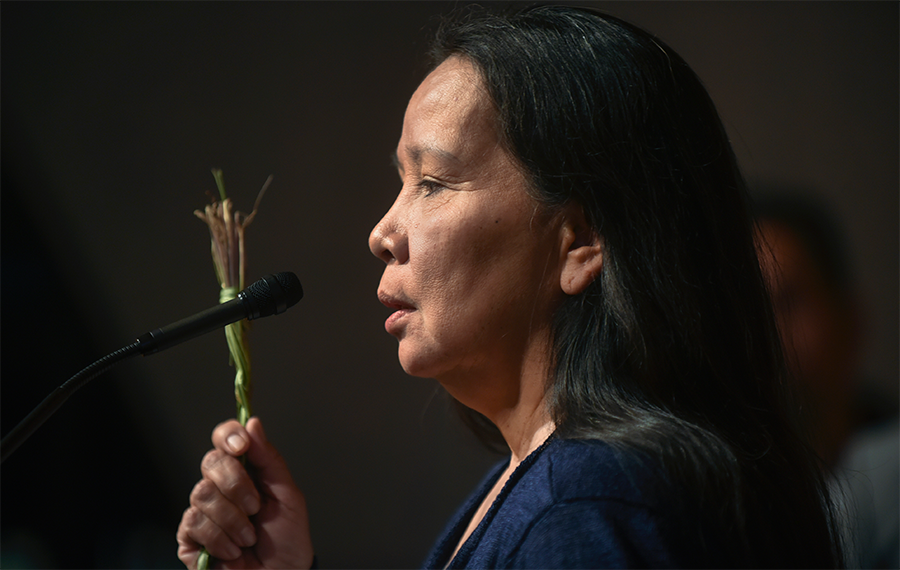

Sometimes residents don’t realize the lasting impact of untreated water, so Aaron and Sheila Craig, a fellow community wastewater facilitator, organize programs to teach them. “We talk about what a good septic system looks like,” Sheila explains, adding that most residents immediately recognize the benefits of investing in a wastewater treatment system. From the educational programs, Aaron and Sheila identify residents who are interested in working toward a solution and invite them to join a local task force.

As outsiders to these communities, Sheila and Aaron aim to facilitate, not dictate solutions.

Since 2002, task force groups have worked closely with the Southeast Minnesota Wastewater Initiative (SMWI), a collaboration with the County Commissioner, Minnesota Pollution Control Agency and Minnesota Public Facility Authority. Through these alliances, local community members benefit from a wide range of perspectives and expertise as they map out water pollution solutions tailored to their specific area. The partnership between SMWI and CRWP eliminated approximately 256,050 gallons of untreated sewage per day for the last ten years. Left alone, that untreated sewage would leach into the rivers and streams of the Cannon River Watershed. Different communities encounter various obstacles due to geography, topography and income, so each task force must tailor its treatment plan to those factors. Some communities live by a bluff, others by the river and some by a stream. If wastewater treatment solutions don’t augment ecosystems like these, they will eventually harm the environment or stop working altogether. As a result, each plan takes three to five years to implement. Sheila and Aaron use their expertise to make sure the infrastructure in each proposed plan remains intact; they also educate the various task force groups on proper maintenance. CRWP envisions wastewater solutions as the answer to ensuring the health of the Cannon River Watershed far into the future, and sees clean water as an opportunity for communities to band together. Through their work, task force members develop friendships and gain prestige in their communities as the protectors of the water and their towns’ livelihoods.

Top-down approaches from untrusted outsiders have left communities suspicious of water treatment plans. Because of this attitude, Sheila and Aaron often encounter resistance to their initiatives.

Vocal community members can turn the tide with a single protest or a few negative remarks at a meeting, even after Sheila and Aaron have dedicated weeks to education and task force formation. CRWP understands that community members come to wastewater problems with a mix of hope and fear. Ardent resistors are deeply invested in the place they call home, so Sheila and Aaron work twice as hard to involve them in the work: “We try to look for difficult people to form our task force. We often handpick someone who is opposed to the project. If [your opponents] aren’t at the original table, they’ll oppose you and spread rumors, so it’s important to involve them and get them to understand the project on the grassroots level.”

In one community, a task force member spoke out against the wastewater management technology the rest of the group wanted. Instead of outvoting him, the task force engaged him in conversation and found a compromise.

“Sometimes it’s about slowing down the process,” explains Aaron. Low-income communities in the Cannon River Watershed constantly face dilemmas about which problems are most pressing and require their town’s limited funds. “Sometimes counties resist us because they see CRWP pulling them away from things they really have to get done,” Sheila says. When Sheila and Aaron face a particularly challenging time finding enough members for a task force, they’ve learned to look for one outgoing person who is comfortable knocking door-to-door and giving out their phone number to people who want to know more or are interested in participating. Finding one respected ally in the community often convinces resistors to trust CRWP. Sheila and Aaron are adept at identifying people with different skills and personality traits to create a well-oiled machine of community members who complement one another. For example, Aaron looks to counterbalance charismatic members with someone who is detail-oriented, pays attention to numbers and can manage timelines.

By connecting wastewater educators to invested and engaged community members, CRYP eliminates ineffective top-down answers. In its place, the organization builds relationships among neighbors and connects people to the natural world, channeling those bonds into lasting solutions that rural towns can commit to over the long term. The process to educate a community, form a task force and guide members toward a community-generated plan can be arduous and frustrating; however, by investing in grassroots problem-solving, CRYP bolsters long-lasting devotion to water health from communities along the Cannon River’s banks.

Cannon River Watershed Partnership is a recipient of the Bush Foundation’s Bush Prize for Community Innovation

Produced in partnership with the Bush Foundation

to showcase the culture of innovation

behind its Bush Prize winners.

Contributors