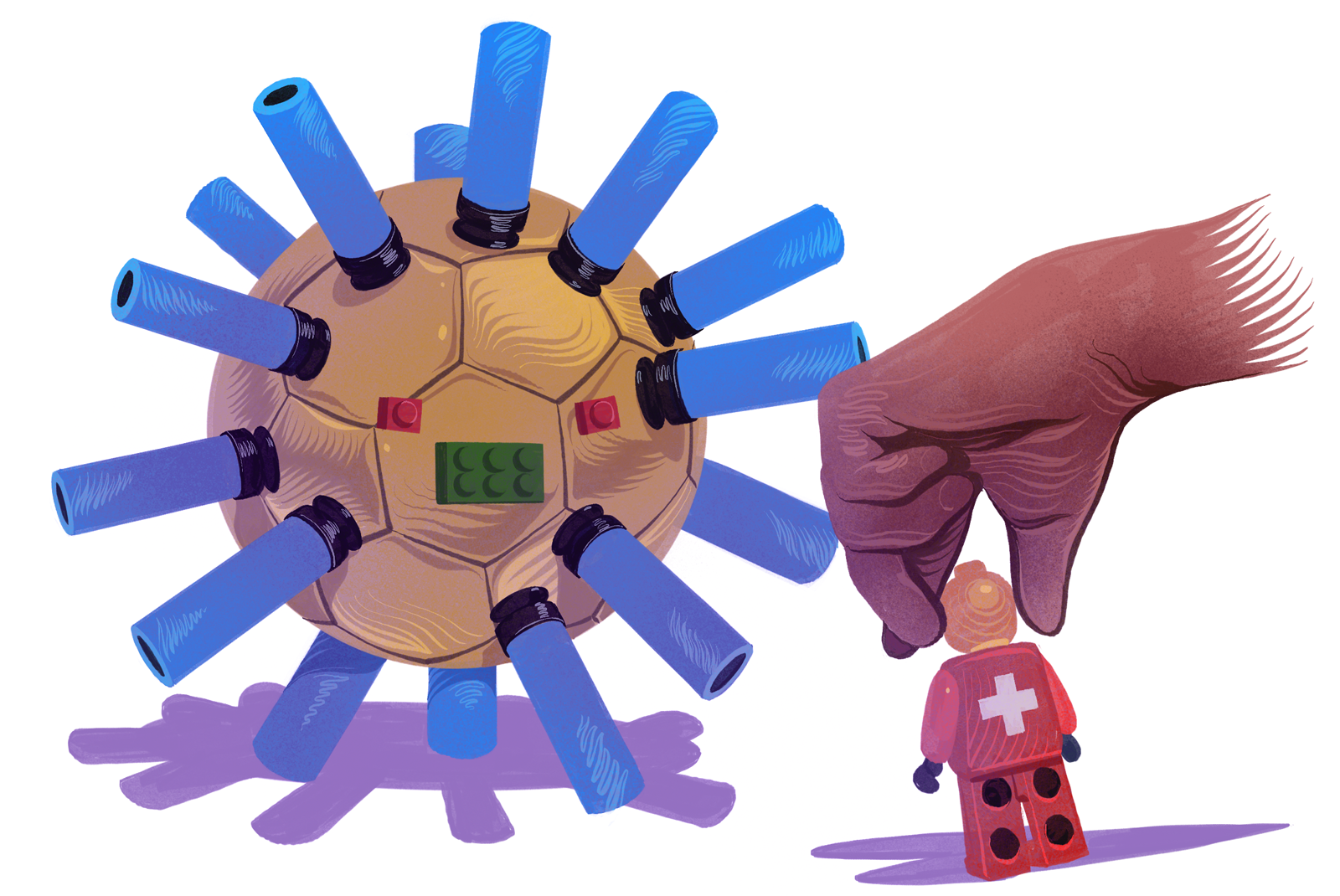

Three weeks ago–another era, it feels like–I was reading the news while my preschool-age son played with his Duplo Legos. I jolted to attention when he made a Lego person jump on an assemblage of colorful bricks, all different sizes, and yell, “I’m going to get you, coronavirus!”

That morning, I had dropped off my older son at the door of his Kindergarten classroom and left the younger one happily racing Hotwheels cars on the carpet of his preschool classroom. My husband and I knew that Governor Walz was considering closing schools to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus, but nothing had happened yet. For several evenings, my husband and I had agonized over whether we should send the children to school. We debated the now-obvious virtues of overreacting against sensible precaution. In those days, we struggled to rationalize what action to take as conflicting stories about the virus emerged each hour. Although our children were within earshot, I had assumed that Paw Patrol–a colorful, dystopian cartoon about a team of pups, each with their own emergency vehicle, who save whales from oil spills and educate human campers about fire safety–consumed their attention. Watching my son play at “beating the coronavirus,” I realized I had been wrong.

I watched my son play out the narrative of coronavirus versus Lego man. In his version, the Lego man destroyed the coronavirus by stomping on it until the plastic bricks broke apart, scattering across the carpet. That night, I told my husband that we needed to talk about the virus after the children went to bed. I felt uneasy watching my son process the uncertainty and dread he perceived in his father and me.

Our plan worked for two days, until Governor Walz announced school closures. That evening, my husband and I found ourselves explaining how a virus spreads and that everyone needed to stay home to “keep our germs to ourselves.” All my children heard was: no school, no park, no playdates. Distraught, the preschooler wanted to know if Spiderman could stop the virus. I wondered what, exactly, hinged on my response. “Probably,” I said, cautiously. Seemingly comforted by my answer, he went to his room to play.

“When will we go back to school?” my kindergartener asked quietly, concern written on his face. A tricky thing about parenting is knowing what, and how much, to say. I realize now that I have let my children tell me what they need from me. My younger son needed Spiderman; my older son needed a fuller explanation. I told him that in New York City, there were more sick people than doctors, that they were running out of beds, and that we needed to stay home to stop the virus from spreading. To illustrate this spread, I opened my news app and showed him the U.S. map that I check each evening: red dots, of different sizes, representing infections. My son studied the map and observed that there were many dots. His logistical questions let me know that our conversation was providing the information he sought. He asked me if hospitals were adding floors. I showed him photos of the hospital tents set up in Central Park. I showed him images of doctors in full PPE. He called them “the rescue team,” a term he learned from Paw Patrol. I realized then that a popular show in our household had already prepared him for the scenes in New York City.

I told him to play with his brother. I needed to think about my response to each child, about the possible repercussions of my responses. A while later, both children called me to their bedroom, as they often do, to show me their latest Lego creation. “It’s a hospital on wheels,” my kindergartener said. His younger brother showed me the Lego people each on their own brick bed, and the team of Hot Wheels doctors who moved the hospital through the neighborhoods of their room. They met Buzz Lightyear at the play table, the cast of Sesame Street standing on the bookshelf, and the fire engine parked under the bed.

Watching my sons work their way through an imaginary pandemic, triaging patients and dropping healed ones back at their homes, I felt touched by their caring and sense of purpose. Then, I felt angry that their play involved solving problems that should never have happened, that can be prevented by responsible governments.

I want my children to learn to hold systems and governments accountable. I also want them to understand that their lives are connected to millions of others, human and non-human, and that their actions matter. In our home, we play out the COVID-19 pandemic with Legos, always imagining an outcome in which everyone is healed. I don’t tell them about the deaths. I need them to emerge from this with a sense of responsibility shaped by the understanding that our happiness depends on caring for one another.

I imagine millions of parents and children around the world playing out the pandemic, in different ways, but always with an ending that leaves us room to grow.

Read More

Victoria’s story is part of Pollen’s “Are You OK?” initiative, a collection of stories, art, and virtual gatherings that documents how our collective community is processing and healing during the this global health and financial crisis. Check the collection regularly to hear from our creative community as we keep up with the changes and challenges before us.

Contributors

We ask that you support these artists by donating to them and the work they are passionate about.

Support Andrés Guzmán via paypal at andguzmail@gmail.com