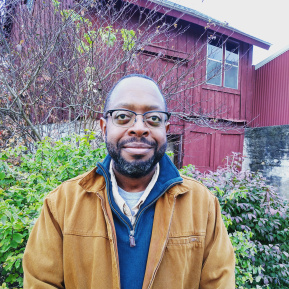

Story by Michael Kleber-Diggs | Photography by Adja Gildersleve | Illustration by Terresa Moses

Me’Lea was, by that point in her career, already a full-time activist devoted to black liberation and she’d just learned Philando Castile was killed by a police officer in Falcon Heights. Her tears were salted by anguish and sadness. Frustration and fatigue were in there too—not even eight months earlier police had killed Jamar Clark in Minneapolis. Leaving town at 500 knots made the gratuitous loss of another black life more difficult to manage; Me’Lea’s pain was magnified by the expanding distance. A kind of helplessness arrived. When you love your community as she does, how else should you feel as you leave it just when you’re needed most?

There was, at the same time, relative safety in the sky. The city and its inhabitants, its dramas and disturbances, they all seemed different when viewed from above.

The distance offered a perspective not easily accessed down on the ground. In spite of her grief, Me’Lea pressed into action. She began rough sketches toward an audacious idea—arrival to liberation requires departure, exodus.

She says this at the Association for Black Economic Power’s stylish but spartan offices in the Harrison neighborhood of Minneapolis’ Ward 5. As she speaks, she’s sitting beneath a banner for Village Trust Financial Cooperative, a credit union named by residents of North Minneapolis. Me’Lea and others are founding Village Trust, and she will lead it when it opens in 2019.

In many ways, starting a black-led financial cooperative is trailblazing work. Which is fitting because Me’Lea is a descendant of trailblazers. Post-emancipation, her ancestors were among the first blacks to migrate to Minnesota. They came from Kentucky in response to an ad posted by Scandinavian farmers. Generations later, out in the Bay Area where Me’Lea was born, her father was a successful software engineer, or, as she calls him, a Silicon Valley O.G. As a child, Me’Lea divided her time between California and Minneapolis, deciding to settle here.

Me’Lea herself has trailblazing instincts. After college, she led a hardwood flooring company to impressive revenue growth even during the housing crisis. She was content in her life as an entrepreneur, but felt called to serve her community when Mike Brown was killed in Ferguson, Missouri. Me’Lea attended a small and peaceful protest at the Mall of America. As a result of her first protest, she began envisioning a better world for her son and decided to work as an activist.

Me’Lea applied for and accepted a job with Neighborhoods Organizing for Change or NOC (pronounced “knock”). Ron Harris, who works today as a Senior Advisor to Minneapolis City Council President Lisa Bender, was employed at NOC at the time and was part of the group that interviewed Me’Lea.

At NOC, Me’Lea brought structure to operations but added value in other ways. “She’s a visionary for sure,” Ron says, “but she wouldn’t be able to pull it off without all the details to go along with it. She knows where to go and how to get there. She’s always trying to innovate and make things more efficient.”

In other ways, starting a black-led financial cooperative is not trailblazing work. Me’Lea often tells prospective members and investors that Village Trust is “walking on a beaten path.” One of the first black credit unions in the ‘30’s was established in the Rondo community and was called Credjafawn. Not only did they have a credit union, they had a grocery co-op, they had a social club, and other cooperative, intertwined entities.

“What happened to Rondo?” Me’Lea asks, then answers. “The infrastructure investment to turn Interstate 94 into what it is, to turn the twin cities into the Twin Cities, and made this place a powerful corporate region, happened by extracting wealth from black communities.” That wealth extraction is part of a long-standing system of exploitation. “We’re on our way to being a net-zero community, a community with zero net value,” Me’Lea observes. “And that’s a community now trending at one trillion dollars of spending power, and that means that none of our money is coming back to us.”

She also knows power concedes nothing without a fight. She understands progress will invite a backlash. “We have to find a way to focus on us without making it an ‘us and them.’ Our strategy has been, we’re black led, but our community can’t just be black.” Me’Lea explains that the purpose is to “create an interweaving of diverse communities for an explicit and clear goal.”

But the first step is building a credit union. And Village Trust is progressing toward completion of that initial step. They plan to open their doors in 2019. They have significant funding from the Jay and Rose Phillips Family Foundation. They have 1,700 members out of the 5,000 they feel they’ll need, and they’ll submit their application for a charter this fall.

Me’Lea is getting ready to complete the transition from entrepreneur and activist to banker—one fueled by an intrepid vision. Back in 2016, when Me’Lea was on a plane mourning Philando Castile, she called the plan she drafted ‘Blexit’ (inspired by Brexit). Later, when Me’Lea returned to the Twin Cities, she attended a community meeting convened to consider how best to prevent institutional violence against blacks. The community determined it could best shape its destiny if it had more influence over financial decisions in North Minneapolis. The idea was to start a credit union, but that idea was always a means to an end. The goal is the same as it ever was—black liberation.

The truth can be denied and hidden and suppressed—in fact it has been—but the truth never goes away.

To Me’Lea, Blexit or black independence makes sense in reaction to oppressive institutions and systems. “These systems don’t work without us,” she says, “and that is the truth behind the concept of Blexit, the concept of exiting systems that benefit from our pain. Our [typical] reaction is to tinker with these systems: ‘oh, it’s broken, we gotta fix it, we gotta press in, we gotta lean in.’ What happens when we just take our toys and walk out the playground? This is the question that I want black people to consider,” By this point she’s speaking with pentecostal cadence and fervor. “Does the monetary economy in the United States work without black bodies, and if it doesn’t, what does that mean for us? How valuable are we?”

In talking about Mike Brown, Jamar Clark, Philando Castile, Sandra Bland, and Rekia Boyd, thinking back on the flight, that day suspended in air, far from home, unable to help, thinking back on the emotions of that moment, Me’Lea Connelly sums it up like this: “Black people don’t have the luxury of being intimidated. What do we have to lose?” Again, she asks and answers:

Click here to pledge your support for Village Trust Financial Cooperative.

Contributors